Violent crime is up.

The pandemic has accentuated poverty and inequity. The consequences may explain the rise in violent crime around the country.

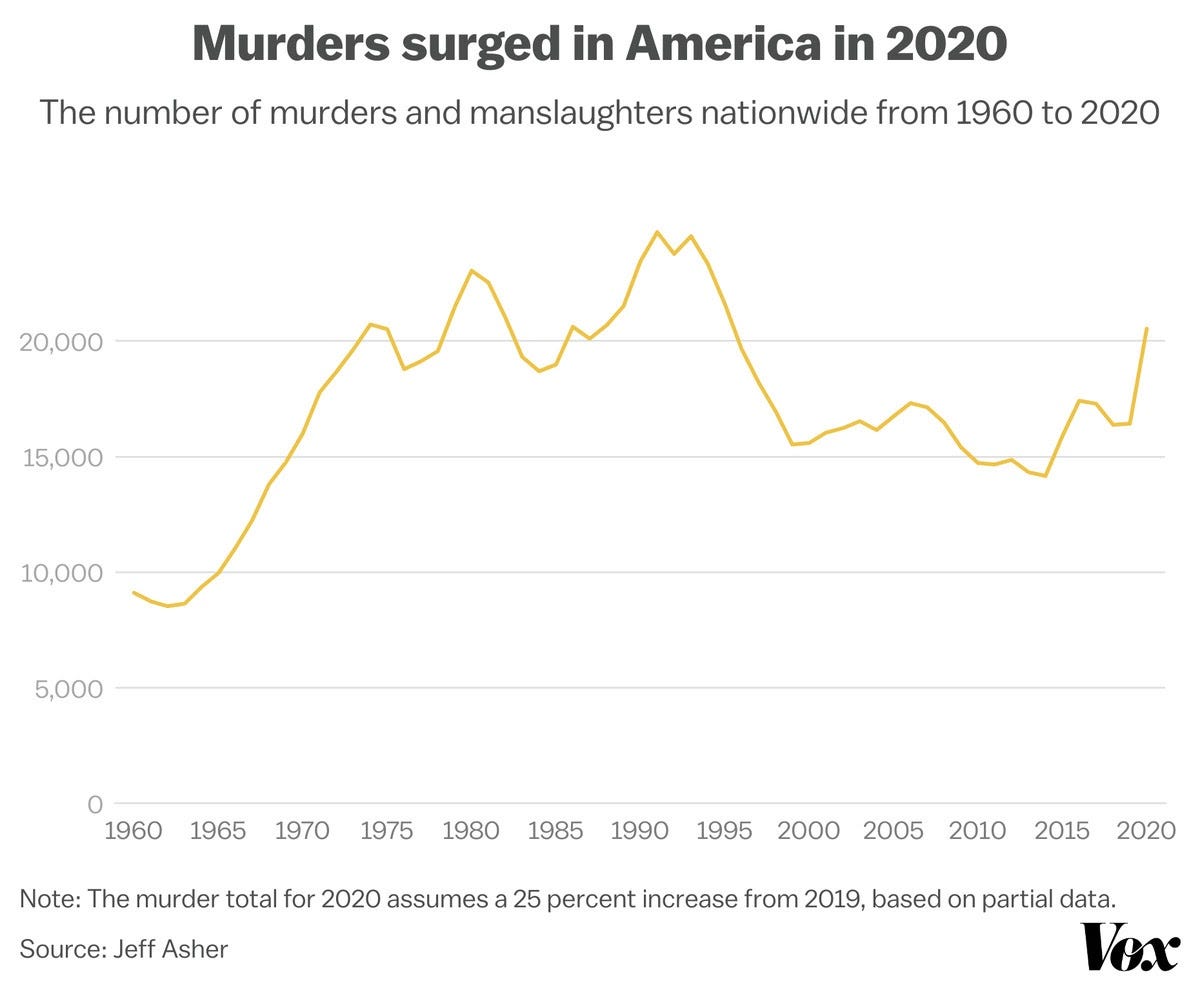

After nearly two decades of consistent decline, violent crime increased dramatically in 2020. Preliminary data from the FBI suggests that murder increased by up to 25% in 2020—nearly 4,000 more murders than in 2019.

As they’ve done throughout the 20th century, interlocutors on the right will undoubtedly use rising crime rates to justify more policing, not less. Which is exactly the wrong approach. And just a year after the murder of George Floyd, that response risks undermining what little progress we’ve made on the excesses of policing that lead to murders like Floyd’s in the first place.

Violent crime is complex. Rather than any single cause, the surge in violent crime is better understood as an interplay of different factors. Oversimplifying complex problems risks dumping our limited resources into simple, obvious-seeming, and ultimately wrong solutions.

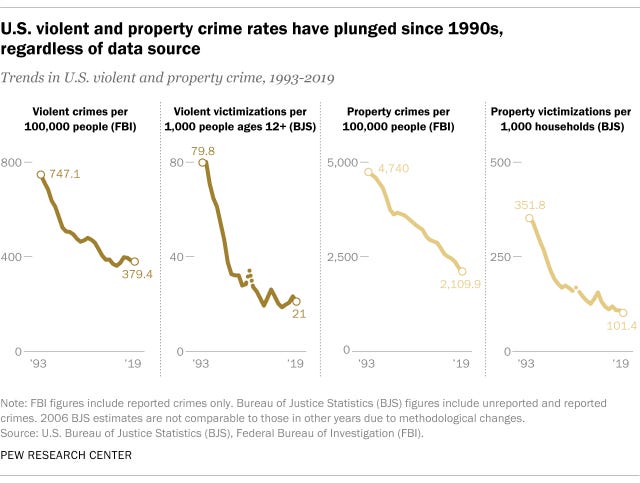

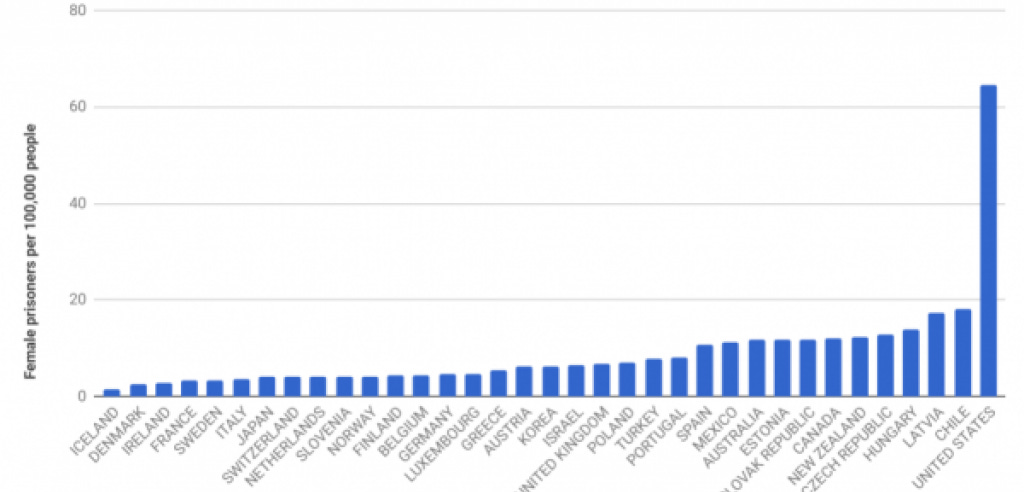

Policing didn’t decrease violent crime before 2020—and it won’t after, either.. For context, the drop in violent crime leading up to 2020 wasn’t relegated to the US. Indeed, murder declined across high income countries. So it’s unlikely to be explained by the uniquely American phenomenon of mass incarceration, a product of the rise in overaggressive, militarized policing and the prison-industrial complex. Indeed, a study by the Brennan Center for Justice suggests that, at best, incarceration only explains about 5% of the reduction in the 1990s. Canada also saw a similar decline in violent crime, without the increase in incarceration.

And yet the rising violent crime rate will inevitably be used to justify more policing by those for whom police and policing has become a matter of dogma (by the way, the same people claiming to support “law and order” and “blue lives” were responsible for an insurrection on the Capitol where law enforcement officers were attacked and beaten).

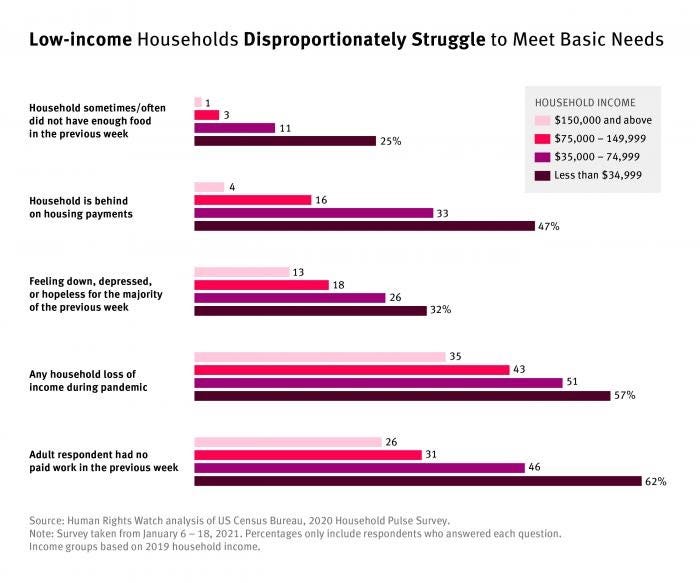

In indulging this argument, we risk missing the obvious one we should be having: 2020 was unlike any year anyone alive has ever experienced. A global pandemic led to a spike in unemployment. Nearly 75 million people lost their livelihoods. Though many ultimately recovered them, the shock of losing a job in the midst of a global pandemic is a profoundly destabilizing, traumatic experience. And many still suffer. In January of this year, 24 million adults in the US were experiencing food insecurity and six million were in fear of losing their homes in the next two months. All of this deepened our collective insecurity.

The pandemic also accelerated the unzipping of an already unequal economy. Billionaires made five trillion dollars, while those at the bottom of our economy suffered. Nearly a third of Americans earning less than $35,000 per year report feeling depressed in the last seven days as they struggle to make house payments and afford their next meal.

It’s not hard to track why this level of suffering would cause crime to spike in 2020–and even into 2021–as we struggle to bring this pandemic to a close. It should be obvious. But there’s a way we ignore the obvious when it’s ubiquitous: we don’t often think about oxygen in the air as a necessary resource. In the same way, the pandemic has become the ubiquitous experience of the past 15 months—so we fail to connect it to all of its consequences.

Violent crime is likely one of them. And yet the conversation about how to take on the spiking violent crime rates in our country will likely reduce back to the debate about policing.

The irony of this is that those advocating for reductions in police budgets aren’t doing so in a vacuum: they’re advocating for those dollars to be invested in taking on exactly the same causes of insecurity that the pandemic exacerbated that underlie so many of its consequences, like crime. Smaller police budgets mean more investment in housing, childcare, food assistance, and income support.

We cannot make the mistake of assuming the simple while missing the obvious. Though it's tempting to assume that crime is a function of policing, investing our resources into policing risks failing to tackle the poverty and insecurity this pandemic has perpetrated, and tackling the crime that likely follows.

You cannot starve someone and then complain when they steal your food. This country continues to promote inequities and its only response has been punishment/incarceration and blaming the individual for making poor choices.

When the awareness came that the pandemic was real, was going to sustain into the foreseeable future and was going to cause many people to die, I had the hope that it would unite us in a common, agreed upon response. After all, the pandemic would affect all of us.

Instead, our official response was that only a few of us were ill and that the pandemic would soon go away on its own, “like a miracle.” The persistent and growing pandemic had an effect on every aspect of our culture and society. Our health, social interactions, learning, businesses and jobs were affected. There were many consequences. I agree with Dr. El-Sayed that increased violence is a consequence of the pandemic. Others include an increase in mental health aberrations such as anxiety and depression and increased suicides. Drug use and abuse and drug overdoses occurred. Economic disparity and homelessness grew exponentially. Many other consequences known and yet to be identified resulted from the contagious virus.

Every crisis creates the opportunity and reasons for major change. Regrettably, those well off socioeconomically were better able to isolate and protect themselves from illness. Those in that demographic felt privileged, special. The areas that needed, demanded immediate action and long term attention and solutions are still largely unaddressed. Now that we can see the pandemic coming under control we still need the understanding of how and why it happened and what can be done prospectively and in real time when we have the next pandemic. Knowledge and leadership are at the top of my list and I still believe in the value of hope.