The Naomi Osaka controversy is about control.

The French Open’s attempt to force Naomi Osaka into speaking to the press follows a long line of major institutions attempting to exert control over Black athletes.

Naomi Osaka is one of the world’s best tennis players—last week, heading into the French Open, she was ranked second globally. Citing her mental health, she announced via social media that she wasn’t going to be doing any press at the tournament.

“If the organizations think they can keep saying, ‘Do press or you’re going to get fined,’ and continue to ignore the mental health of the athletes that are the centerpiece of their cooperation, then I just gotta laugh...”

After an easy victory in her first-round match on Sunday, true to her word, she skipped the post-match press conference. The tournament referee at Roland-Garros (the official name of the French Open) fined her $15,000 for contract infringement (press participation is a stipulation in tournament contracts). But then something unexpected and unprecedented happened: the leaders of all four Grand Slam tournaments (Australian Open, French Open, U.S. Open, and Wimbledon) released a joint statement announcing the fine. The move was intended to intimidate Osaka. In response, Osaka pulled out of the tournament.

Playing tennis and talking to the press are two different things. And when someone as good at tennis as Osaka is bullied by the four most powerful people in the sport over something other than playing tennis, they reveal that it’s not about tennis. It’s about control.

And there is a long, painful history of powerful sporting institutions attempting to control athletes generally—but particularly Black athletes. It goes back to well before Osaka was even born.

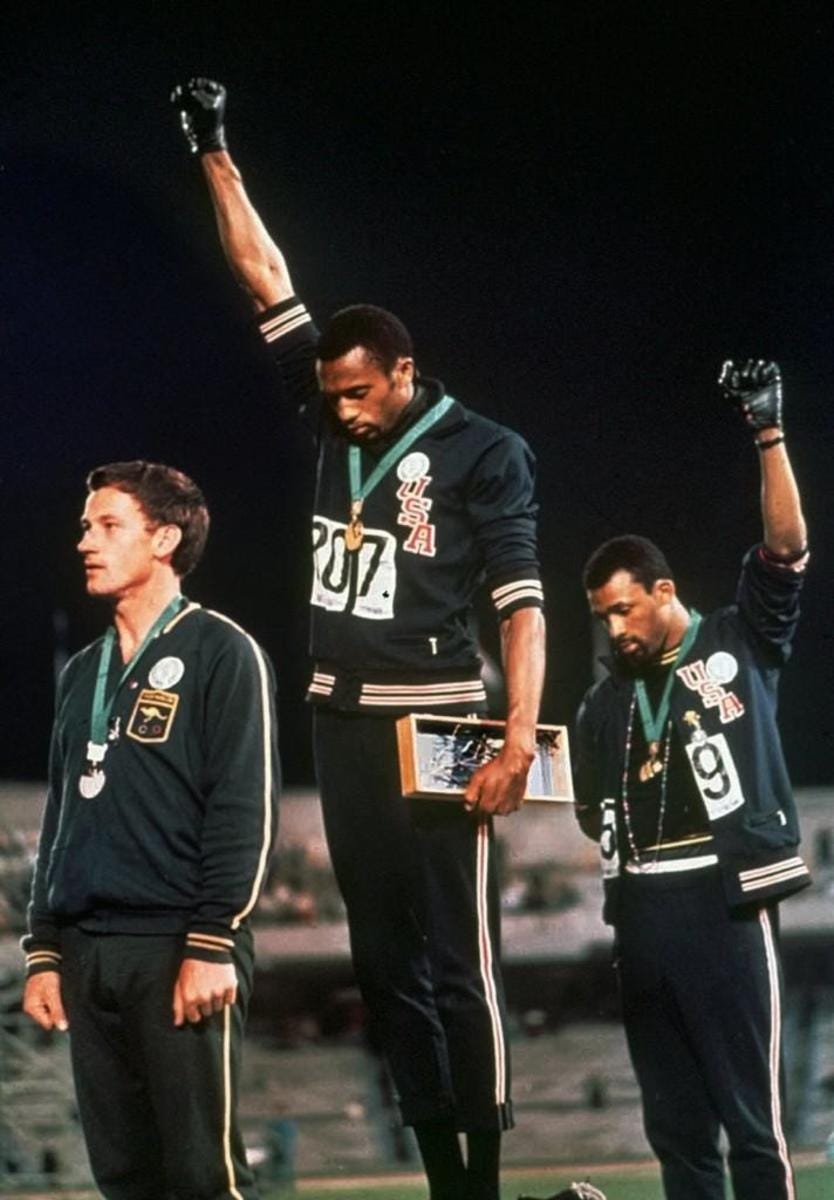

During their medal ceremony in the 1968 Olympics, sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised gloved fists to the air in a Black Power salute. International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage (also an American) quickly ordered the U.S. Olympic team to suspend Smith and Carlos, threatening to ban the entire U.S. track and field team if his order wasn’t followed through. The gold and bronze medalists were expelled from the Olympic games. It wasn’t about sports—it was about control.

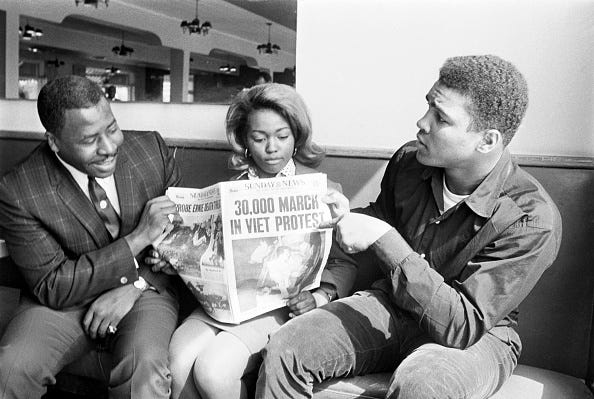

In 1967, Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted into the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector, citing his religious beliefs. After he was arrested for refusing the draft, the New York State Athletic Commission stripped him of his heavyweight title and his boxing license, prompting other commissions to follow suit. He was locked out of boxing for three years. He wouldn’t be reinstated until the Supreme Court ruled in a unanimous decision in his favor in Clay v. United States. It wasn’t about sports—it was about control.

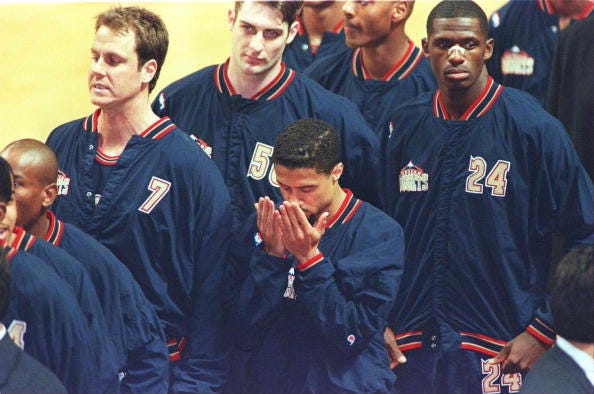

Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was suspended by the NBA for refusing to stand during the national anthem in 1996. He was traded the next season. And of course, most recently, Colin Kaepernick was blacklisted across the NFL for taking a knee in support of the Black Lives Matter movement during the anthem. He hasn’t taken a snap as an NFL quarterback since 2016. It wasn’t about sports—it was about control.

These athletes weren’t punished for anything they did on the track, court, or field—but because they dared to speak (or even kneel) against oppression.

But the institutional pursuit of total control over Black athletes doesn’t stop at censure over their activism. Every time Michael Jordan walked onto the court in his iconic black and red Nike Air Jordan 1s in 1984, he was fined $5,000. In 2005, NBA Commissioner David Stern announced a mandatory off-court dress code that specifically banned durags, large jewelry, sneakers, Timberland boots, jerseys, jeans, and hats—specifically targeting Philadelphia 76ers star Allen Iverson. He rebelled by wearing longer shorts on the court, violating another dress code requiring shorts not to extend past 0.1 inch above the knee. Iverson’s 76ers were fined $10,000 per game because his shorts were too long. And then there was another Black tennis star, Serena Williams, whose “catsuit” was banned by Roland-Garros in 2018. Williams, making her debut after a challenging pregnancy during which she had developed a blood clot that almost went undetected by medical personnel, had dedicated the catsuit to “all the moms out there that had a tough pregnancy.” French Tennis Federation President Bernard Giudicelli’s justification? “You have to respect the game and the place.”

But what about respecting the athlete? Osaka has struggled with mental illness. She’s said that requiring her to perform both on and off the court adds to her struggles. Shouldn’t the sport put the wellbeing of their stars—especially their health—first? But Osaka shouldn’t even need to prove she has a legitimate reason to choose not to participate in post-match press. After all, it’s a tennis tournament, not a debate.

Why do so many major sporting institutions care so much about controlling Black athletes? It gets to a bigger issue at the core of the professional athletic business model. Sporting institutions make money because people pay to watch the greatest athletes in the world ply their trade. Those audiences are predominantly white. The people at the top of these institutions, be it the Grand Slam tournaments, the NBA, the NFL, or the International Olympic Committee, attempt to control Black athletes to comport with some artificial sense of what they think their white audiences may deem respectable.

The irony of this latest attempt by Roland-Garros and the tennis elite to force Naomi Osaka to speak to press is that Black athletes are routinely punished for the statements they make—whether in support of social justice, or simply reinventing fashion. But in the case of Naomi Osaka, she’s being punished for not making a statement. Which just goes to show that it’s not about what’s said—it’s about who gets to decide what is said, when it’s said, and to whom it's said.

It’s not about sports—it’s about control.

It’s always about control, either shut up and play or we only want you to talk about sports. When we address institutional and systemic racism, we need to address the holdover from slavery — controlling Black bodies, thoughts and words. We still call their employers “owners” and justify bad treatment from audiences (fans don’t spit on people) by saying they are well paid so should suck it up. There isn’t enough money to put up with dehumanization, yet when athletes protest, they are given that message. Good for Naomi and all athletes and entertainers who put their well-being first. We can help by supporting their right to control themselves.