The state of Medicare for All in 2021.

Momentum is building. But these three obstacles loom over the horizon.

Last Wednesday, Rep. Pramila Jayapal introduced the Medicare for All Act of 2021 in the House with more than half of the House Democratic Caucus backing the bill. Along with the usual suspects, the bill’s unlikely supporters included congressional veterans known better for their legislative power than their progressive ideals, including 17-term Congressman Frank Pallone who chairs the powerful House Energy & Commerce Committee. Pallone had blocked a hearing on Medicare for All during the last Congress. This go-around, he’s not just a co-sponsor, he’s promising a hearing, telling the Washington Post: “The goal of universal coverage is going to be at the center of everything we’re going to do on health care.”

And yet, considering this moment, Medicare for All’s momentum is little solace for how much further we should be. After all, we are (insha’Allah) nearing the end of a pandemic that took more than 540,000 American lives and waylaid our structurally unsound healthcare system. We watched nurses, doctors, and hospital workers care for sick and dying people in garbage bags and months-old masks. If hospitals weren’t bankrupted or shut down by the pandemic, they were stuffed with far more patients than they could manage. We watched as nearly 15 million people lost their health insurance while the insurance industry made billions. Given all of this, it’s hard to understand how people—and their elected representatives—aren’t absolutely clamoring for Medicare for All right now.

Meanwhile, we do have a Democratic President…but he’s said he’d veto Medicare for All if it came across his desk. And though, as I’ve written in this newsletter, he’s led us toward some incredible progress on poverty, he’s also sought to address our COVID-19 healthcare failures through subsidies to the very same insurers who’ve left us in this predicament in this first place.

Some think that achieving Medicare for All is simply a matter of political jiu-jitsu that progressive politicians lack the temerity to pull off. I think they misjudge this moment. Though we have incredible momentum, we don’t yet have the profound political consensus we’ll need to achieve Medicare for All. The house built of straw is the first to be blown down.

There’s more organizing yet left to do. Though we’re unlikely to achieve Medicare for All during a Biden Presidency, what we do with this moment may decide whether we achieve it in the future. Indeed, this must be the moment we build the power and political consensus that will yet achieve Medicare for All.

Toward that end, it’s worth stepping back and taking stock of some of the most challenging obstacles ahead--and how we can take them on.

The GOP is no longer organized around ideology—but identity.

It’s become something of a trope to say that “we’re more polarized than we’ve ever been.” Yes, the two parties have polarized tremendously—but the nature of partisanship isn’t simply ideological.

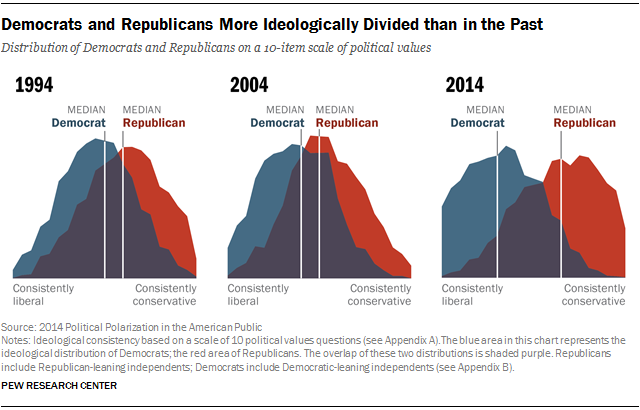

The last three decades of American politics has seen a long period of increasing ideological assortment on issues. Democrats lined up on increasingly liberal and progressive lines while Republicans lined up on increasingly conservative lines. Pro-choice Republicans or Democratic NRA members have become political unicorns.

That was, of course, until Donald Trump broke the Republican party.

Indeed, beneath the ideological polarization had been a series of demographic and geographic trends that were more important to predicting partisanship than any ideological debate ever was. Republicans were getting older, whiter, and more rural. Democrats were getting younger, darker, and more urban. Since Trump broke it, the Republican party has seemingly abandoned ideology and policy altogether, opting instead for a never-ending culture war over the most important issues of our time—like which books Dr. Seuss’s estate will publish, or the cancellation of “Mr.” Potato Head. But the culture war masks a broader anxiety within the Republican base—that of an increasingly insecure future, that looks less and less like the security of the American past.

This is where our current understanding about Medicare for All breaks down. We assume that Republican voters categorically oppose Medicare for All on ideological terms—because it's an anathema to Republican ideology. But there is no Republican ideology anymore. In fact, a 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation and Cook Political Report poll of key battleground states found that only 2% of Trump supporters said they would switch their vote if Donald Trump were to support Medicare for All. If we try to understand the current GOP through a traditional ideological lens this makes no sense.

That’s because it’s no longer about policy—it’s about who advances it. Just because Republican voters might accept Medicare for All from Donald Trump doesn’t mean they accept Medicare for All. This has historical precedent. Take the last serious push for health reform as an example. The principles beneath the Affordable Care Act originated out of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, way back in 1989—and was passed in its first form in Massachusetts by Republican governor Mitt Romney. And yet it was viciously opposed...not on ideological grounds, but on partisan ones.

Why? Partisan identity matters more today than ideology. And for today’s GOP partisan identity has become a smokescreen for race.

White identity politics opposes expanding universal public goods in a diverse society.

In her excellent book, The Sum of Us, economic policy expert Heather McGhee argues that though the societal cost of white supremacy is borne most deeply by Black people—the cost is borne by white people, too. To demonstrate her argument, she uses the historical metaphor of public pools in the South. Rather than open their swimming pools to Black children after Brown v. Board of Education forced them to integrate, municipality after municipality simply paved them over.

Racism has already extracted a healthcare cost on poor white folks. One of the most powerful provisions of the Affordable Care Act was the expansion of Medicaid. Though it is primarily federally funded, the program is operated by the states, and the ACA left the choice to expand Medicaid to state governments. Despite being some of the poorest in the country, most Southern states chose not to expand Medicaid, leaving their poorest citizens—Black AND white—sicker for it.

Consider this example: Kentucky and Tennessee are alike in almost every way...except that Kentucky expanded Medicaid in 2013. Though Kentucky had begun with a higher rate of uninsured, by 2015, the rate of uninsured in Kentucky tumbled from 21% to just 8%. Meanwhile, uninsurance in Tennessee was nearly twice as high, at 15%.

Ultimately, the logic of racism would rather deny public services to anyone than provide public goods for everyone—so long as everyone includes People of Color.

Corporate money in politics.

There is simply no way around this fact: we don’t yet have real universal healthcare in this country because our political system allows corporations to shape both our discourse and political priorities in their favor.

Indeed, as Historian Jill Lepore chronicled in her New Yorker feature article “The Lie Factory,”

the political consulting industry itself was, in part, born out of a campaign to defeat universal health reform in California in the 1940s.

Following his own harrowing experience with a serious kidney infection, then Governor Earl Warren, proposed a statewide health insurance program. Worried for their profits, physicians working through the California State Medical Association (think California’s version of the American Medical Association) hired Campaigns, Inc., the country’s first fledgling campaign consulting firm, to defeat the effort. They were relentless. Campaigns, Inc. deployed over 9000 doctors with prepared speeches. They bought over 40,000 inches of advertising in over 400 newspapers to extol Californians to buy their own private health insurance through a manufactured “Voluntary Health Insurance Week.” They mercilessly lobbied newspaper editors—who sold all those ads to the firm—to oppose the bill. They sent millions of pamphlets titled “Politically-Controlled Medicine” to homes across the state. And they defeated the bill by one vote.

In the process, they invented a new smear: “socialized medicine,” which would be deployed to great effect against every single effort to pass health reform in the future. They started with President Harry Truman’s efforts to pass a national health insurance plan just a few years later—a campaign for which the AMA would spend $5 million, an unimaginable sum for those times.

Today, the disinformation about national health insurance comes mainly from the “Partnership for America’s Healthcare Future,” who ran incessant ads against Medicare for All throughout the 2019 and 2020 primary season. As soon as President Biden secured the nomination, they shifted tack, running ads against the Public Option instead. These ads have power, shifting public opinion against Medicare for All, and reframing the debate around industry talking points. Their go-to lines about “choice,” and “cost” mask the impact that the private insurance industry itself has on limiting our choice of doctor or inflating healthcare prices.

But ad spending isn’t the only way healthcare corporations translate their money into power. The insurance industry spent nearly $152 million last year alone employing 845 lobbyists (two-thirds of whom were former government employees). In the 2020 cycle, they gave $120 million dollars to politicians across both sides of the aisle.

That money buys them influence among lawmakers. Most obviously, it keeps Democrats who might otherwise support Medicare for All off the bill and keeps Republicans fighting it. But more insidiously, it keeps lawmakers who’ve signed onto the bill from doing all they can to advance it. Indeed, several of the 2021 bill’s co-sponsors, even some who claim themselves to be among the bill’s most important proponents, perennially run campaigns that are flush with cash from the very industry they claim to oppose.

How we win Medicare for All anyway.

My book with Dr. Micah Johnson, Medicare for All: A Citizen’s Guide, features an entire chapter called “Organizing vs. Advertising” for a reason. These obstacles aren’t insurmountable—but the only way around them is through them. If we want Medicare for All, we’ll have to organize for it.

Veteran labor organizer Jane McAlevey argues in her book No Shortcuts that organizing isn’t simply about the short-term marshaling of people-power toward a particular outcome, as we do during a political campaign, for example. She calls that “mobilizing.” Rather, real organizing is about the slow and steady work of helping people find themselves in the struggle. Though we may not get Medicare for All during a Biden Presidency, we don’t have the power to mobilize for it, anyway.

Rather, we need to build that power through deep organizing. That includes the incredible work that organizations like the National Nurses United, Be A Hero, the Center for Popular Democracy, People’s Action, Physicians for a National Health Program, Public Citizen, Social Security Works, and so many others do on the ground. But it also includes the discussions we have with our family and friends, our co-workers, our classmates, our neighbors, and so many others, every day. It’s in helping people connect the insecurity they may feel about their finances or their healthcare to the broader brokenness of our healthcare system—and the greed of corporations that maintain it.

Though negative identity-based partisanship has gripped the Republican party, our broken healthcare system puts so many of the rural communities in which they live in a vice grip, too: even folks privileged enough to have health insurance in rural communities are losing healthcare access through hospital closures. We must do the work of connecting those experiences to the reform we seek.

And rather than ignore race and racism, we need to call out the ways it has been used to divide us. This is the key idea within the race-class narrative that leaders like Heather McGhee and Jane McAlevey have championed and activists across the country, and specifically in Minnesota, have deployed to bring communities together. It leverages a direct and honest engagement with race and the destructive power of racism to identify how it’s been used by those who profit off the status quo to divide people. Indeed, Medicare for All would benefit white and Black people across this country alike—but the healthcare industry will continue to drive a wedge into our efforts to achieve it by weaponizing division against our movement.

And finally, beyond Medicare for All itself, we have to organize around reforms that curtail the power that corporations wield in our democracy in the first place. We also have to hold our politicians accountable for the ways they choose to fund their campaigns. Wildly effective fundraisers like Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have demonstrated how a candidate can run on her ideals without the corrupting money of corporations and succeed. We need to demand that kind of integrity.

Medicare for All is our future—if we’re willing to build it.